I wish I were a battery, so I could plug in and recharge. I posted this on Facebook today, and a kind friend responded, as one does, that humans recharge by unplugging. I said I didn't know about that.

I do wish I could recharge by being plugged in. That would be so much easier than plowing through all the hanging fronds and threads of suggestions about self-care. None of the social service agencies with which we're connected allow parents any time for self-care. It's anathema to the entire system of caregiving. Self-care is, indeed, a pleasant fiction that others indulge in for my sake.

Walks, runs, massages, mani-pedis, dinners out alone, time with friends. Those occasions arise, yes, but I've gotten to the point after 20 years of this at which self-care seems a distant reach.

To be honest, for me, self-care is ignoring things (paperwork mostly) that I just don't feel like doing today or any particular day. So I let my mail pile up, open it and let some of the stuff pile up elsewhere, shuffle it into different piles, continue to pick out the items that seem the most important or urgent or both, and letting the rest of it sit. Every 3 or 4 months, I take a day and go through all of it at once.

Tomorrow, I'm driving my daughter back to college in Vermont. Today I grabbed a box and stuffed all of that paper into the box, all the clutter in piles all over my home office. It's satisfying to see it all in one cube.

I've had a lovely summer being a parent one last time to two children: Rob and Edith. Edith has just finished her freshman year at Middlebury, and she definitely needed some additional oversight coming home on a couple of different fronts. The household was full again. We were one smoothly oiled machine--walking the dog, taking care of the cats, dishwasher dirty & clean, garbage out, boxes cut up, groceries, dinners made. Oh, yes, and I taught her to drive this summer--all 60 of the required hours. She takes her driver's test tomorrow on our way to Vermont. That's a long story and not that interesting.

She's going to take an internship, she says, next summer. As I told Rob tonight at dinner when he seemed glum, now is the time for each of us must separate to grow. We can receive emotional sustenance from each other, but, eventually, we grow by coming apart. We'll always convene again as

a family, we'll always spend time together.

Yesterday I sent an essay into a call for submissions, an essay I've been working on in fragmented time all summer. I hope it's good enough. Today, I submitted another essay in which I have more confidence. I need to submit work a whole lot more to make any progress. I need to write more and complete long-term projects.

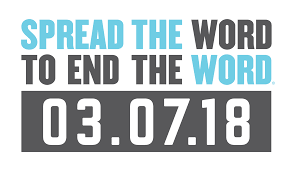

Rob needs to take his college "challenge" courses at Montgomery College. He needs to go to Spirit Club, his disability gym. Rob needs to write more poetry and perform it at some local reading series. And, most importantly, he needs to continue to advocate for health care and disability rights.

And that's where I've found my greatest respite and self-care: advocacy. Last December, as he was transitioning from high school, Rob identified advocacy as one of his transition dreams. So I signed him up for Little Lobbyists and for the Rare Action Network. We've plugged into a number of other advocacy groups as well, looking for our home.

When I'm advocating for health care, for disability rights, for funding for rare disease, I feel alive. I never thought advocacy would be for me until I had to jump into it to assist Rob and his own dreams. Its community. It's reassurance. It's projecting the better parts of me outward in service of others. This selflessness feels better to me than any of the other "selflessness" in which I've engaged as a caregiver.

Abnegating my "self" simply as a mother, on a routine basis has a draining effect on me. In the WDC area, when people talk about being "plugged in," they mean they know a lot of people, that they're influencers. This self-identification as plugged in can seem selfish, a form of bragging, a way of fulfilling personal goals by using other people.

But the advocacy I've found in these last seven months has been a group effort with no thought of personal reward. It's all moms and dads, all parents of children who need us to stay at home, to stay healthy, to thrive. No other "self-care" has been as electrifying to me as this: being plugged in. Like a battery, I'm recharged.

Reposted with permission of the author, Jeneva Burroughs Stone, from her personal blog “Once Upon a Caregiver.” Jeneva is the leader of the Little Lobbyists 16+ community for older teen and adult Little Lobbyists and their families.

Jeneva with her son Robert and husband Roger advocating for Medicaid in front of the Capitol with members of Congress and Little Lobbyists mom Laura.

Jeneva and her family with the Little Lobbyists at a Town Hall with Senator Elizabeth Warren.