Spelling It Out: The ADA and the Right to Community (by Bob Williams)

Bob Williams seated in his wheelchair, which has a mount supporting his communication device. Bob is a white man wearing a white suit jacket with a pink striped shirt and a bowtie.

As far back as I can remember, I have always found ways to express myself that others can understand. It is why I escaped the discrimination others still endure.

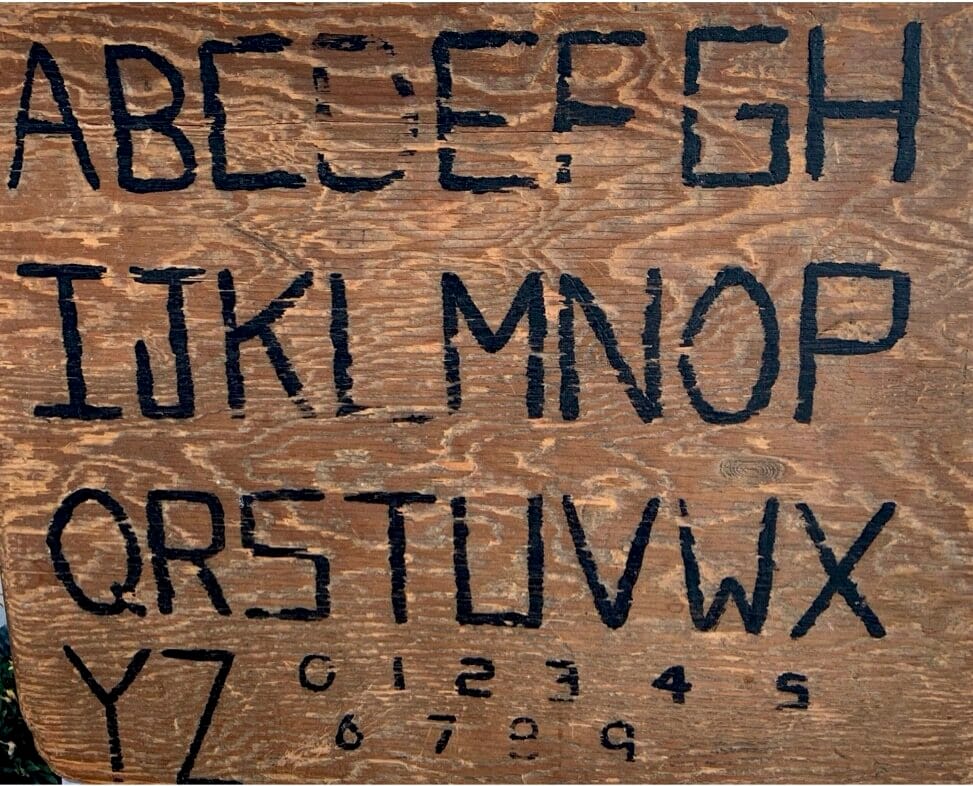

I have significant motoric, and speech, disabilities due to cerebral palsy. On the wall of my office hangs a piece of wood with the alphabet and numbers zero through nine stenciled in black. It is there as a reminder of both the journey I have been on over the past 63 years and the large debt I am paying forward.

I believe my life, while molded by many factors, has been possible by the love and belief that my family and others have had in me. From a young age, I had a ready supply of ways to communicate and connect. My Mom said that she knew I could keep a beat and had things to say when I pretended to lead a band or played 20 questions, beginning as a toddler. At six or seven, I learned to type on an IBM electric typewriter, which convinced my doubtful teacher that I could both read and write.

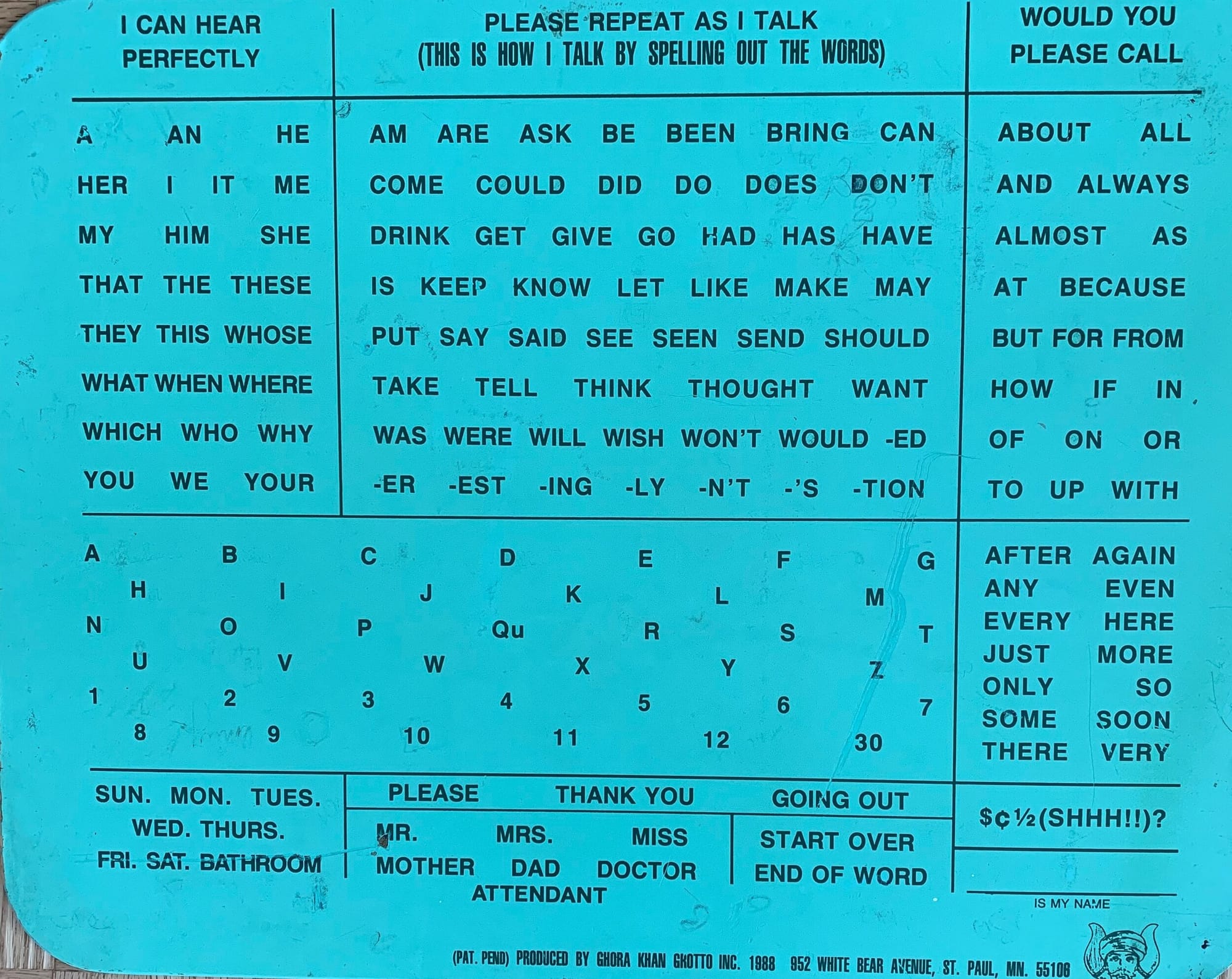

When I was about 15, my camp counselor painted the alphabet in bold black capital letters on that piece of wood hanging on my wall. I pointed to the letters to spell out words and sentences. A year or two later that same camp counselor handed me a green board that had letters, numbers, words, and phrases on it. It was called the Hall Roe Communication Board, named for the man with cerebral palsy who helped design it, and it saw me through high school, college, dating, internships, and my first two full-time jobs. In fact, I used that board to lobby with others to gain passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Bob’s first communication board: a piece of brown wood handprinted with the alphabet in capital letters and the numerals 0 through 9.

Just after the ADA became law, I participated in the Augmentative Communication, Empowerment, and Supports (ACES) Institute at Temple University in Philadelphia. There with about a dozen other people who used AAC, I learned to use my first speech generating device. I have been using successive iterations of this same device throughout my life. After that my life and career took off in directions even I had never before fathomed possible.

ADA AND THE RIGHT TO COMMUNITY

For me, the penultimate purpose of the ADA is best summed up in four words: The right to community. I want to be clear; I did not say “the” community. I said, the right to community: To be a part of, not apart from, life.

Congressman John Lewis’ last words to America, printed in The New York Times on the day of his funeral, were these: “Democracy is not a state. It is an act.” I believe he meant democracy is not just some fancy-sounding noun we use. Not something we should dare take for granted. Rather, it is a verb--the action we all must engage in known as E. Pluribus Unum, each doing of our individual and collective parts to create and nurture. One out of many.

I believe the same is true of community. Community is not merely a place on a map. It is an act that we all must engage in and take responsibility for, together. It is the action of communicating, connecting, and being in community with each other.

I often ask all kinds of people what they see the purpose of the ADA as being. Predictably, they say that it is to eliminate the architectural and other design barriers many of us encounter. I reply this is true as far as it goes. But I then point out that the fundamental aim of the law is to continually chip away at and to eradicate the pernicious, deeply entrenched biases that are the root reasons for these barriers, as well as other forms of discrimination, including speech discrimination.

Progress clearly is being made, but far more work remains to be done. Thirty years ago, when many of us were working on the passage of the ADA, we referred to accessible transportation as the linchpin of community integration.

Today, effective communication is that linchpin. Absent that, there is no community, there is no real integration. Where we live is critical, but merely being present is not sufficient. Absent the opportunity, tools, and strategies we need to communicate, connect, and live with each other, as part of one another, we are all forced to live separate and apart from each other.

A Hall Roe Communication Board. Image of a board with a blue background covered in sections of black type that include commonly used words and phrases, as well an as alphabet.

SPEECH DISCRIMINATION

To this day, there is no question that children and adults who cannot use our own natural speech to effectively express ourselves continue to experience higher risk of unjustified institutionalization, segregation, and isolation; abuse and violence; widely disparate education, employment, and health outcomes; and the routine violation of our liberties, the power to express ourselves, and to decide how we live our lives.

The ADA offers two sets of requirements that I strongly believe we must increasingly leverage to challenge and put an end to it. The first of these is the right to effectively communicate. The ADA requires that people with disabilities that impact their ability to communicate (whether expressively, receptively, or both) must be afforded the opportunity, tools, and supports necessary, in the words of the Justice Department, “to equally and effectively communicate with others.”

The second set of safeguards are those commonly referred to as the “integration mandate” of the ADA and affirmed in the Olmstead decision, which require that people with disabilities not be institutionalized, segregated, or otherwise isolated, and that they must be afforded the opportunities and supports to take part in every facet of the American community.

For too long, far too many children, working age persons, and older adults who need, but lack access to augmentative and alternative communication strategies and related supports have been isolated and excluded from much of life. I believe we can and must shatter the injustice of silence by using both sets of these protections to advance and secure a true right to community.

Communication is never a one-way street. Community is not an island that we exile someone to and declare they are integrated. For too long, we have placed the onus for communicating solely on the person with the greatest challenges. I have seen, as I am certain you have, how this has played out in the lives of many folks with intellectual and developmental disabilities, who I have known, loved, and learned the most from. We must expose and end this most endemic and devastating bias. As Anne McDonald, who spent most of her life on the back ward of an institution in Australia, wrote, there is no way for someone that is speechless and trapped to connect and communicate if others do not help them to make that leap. The ADA, in my view, must become the powerful launching pad that enables us to make that great leap, together.

Image of the Communication FIRST logo, blue and green speech bubble icons intersecting. The intersection is black with white lines that symbolize text.

Bob Williams is the Policy Director of Communication FIRST, and has advanced the rights, opportunities, and supports for children, working age persons, and older adults with significant disabilities for over 40 years, including creating community living services in DC, helping to pass the ADA, and administering the federally funded developmental disabilities and independent living networks.