Jenny takes a selfie in one of the California Assembly buildings in Sacramento. She wears her trademark bright pink glasses, as well as a bright pink blazer. Behind her are the ornate columns, gates and tile floors of a legislative building.

Hi! I’m Jenny McLelland and I’m the Director of Policy for Home and Community-Based Services for Little Lobbyists. My family lives in Clovis, a small city in the agricultural Central Valley of California. My husband is a physical education teacher, and I’m a retired police officer. We have two teenage children - Josephine and James.

In my role as Director of Policy for Home and Community Based Services, I get to help turn family stories into solutions. That means I’ve had to learn a lot about Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services waivers. Medicaid HCBS Waivers are the legal framework that pays for children like my son to get nursing care at home. I want to make sure that any child who needs nursing care at home can get it, like my son James.

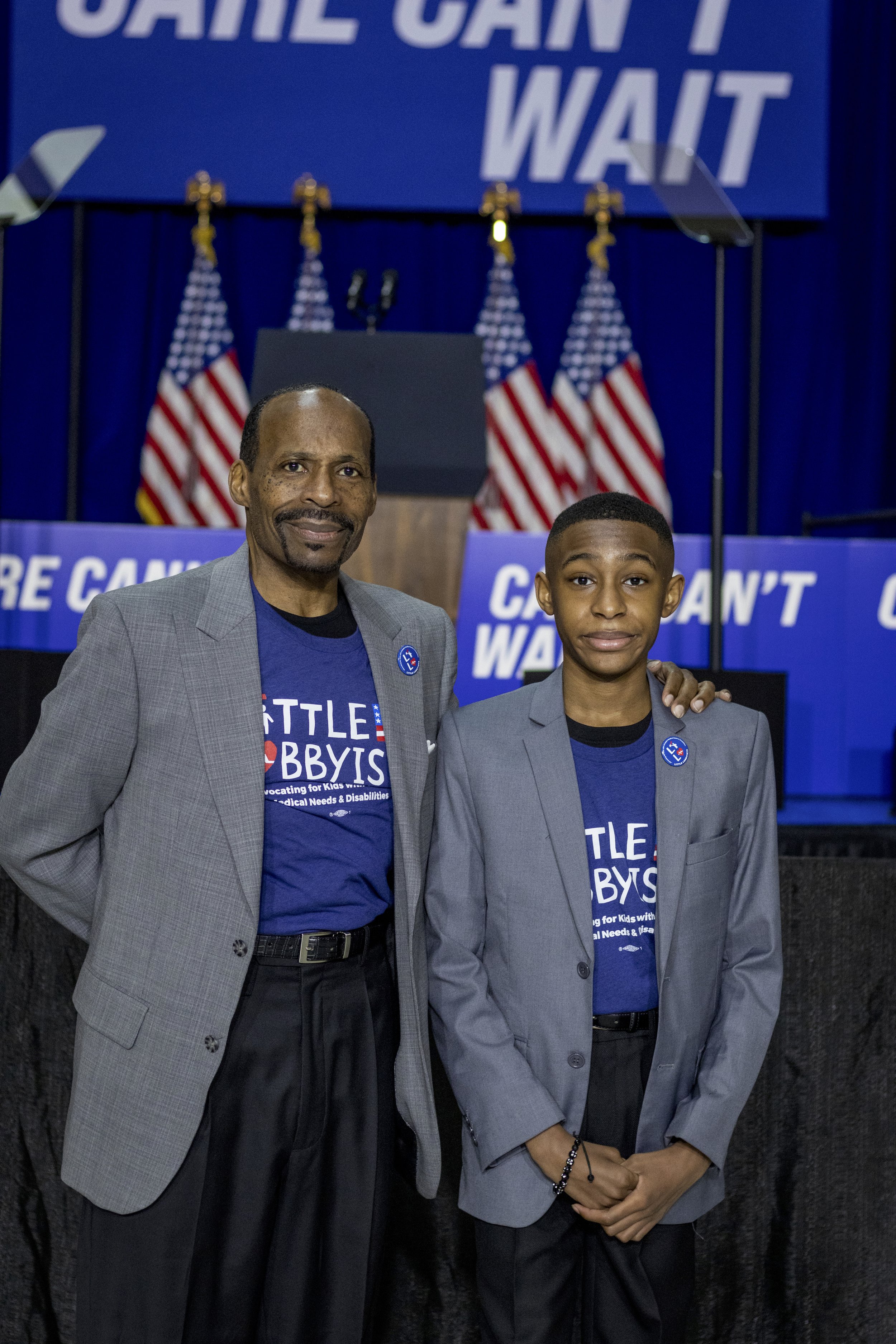

I got involved with Little Lobbyists because of my 13-year-old son James. He’s a really fun kid. He gets good grades, he plays percussion in the school band, and he loves 3D design and printing. James has a rare genetic disorder that affects his airway and breathing, so he has a tracheostomy (a plastic tube in his neck) to help him breathe and he uses a ventilator at night.

My biggest priority as an advocate is to make sure medically complex kids have access to nursing care at home. My son spent most of the first year of his life in an institution because we couldn’t get the support we needed to bring him home - I don’t want that to happen to anyone else.

James (l) and Jenny (r) pose in a hospital room at discharge. Jenny is wearing bright pink eyeglasses and has chin-length blonde hair. James is wearing a sage green Pokemon shirt and holds a paper shopping bag and a robot. Behind them are an unmade hospital bed, and a variety of medical equipment and monitors.

There are two equally important sides of advocacy: telling stories that help people understand what life is like for disabled kids, and using those stories to solve problems. Little Lobbyists does a great job of helping families tell their stories in a way that puts a human face on a complicated policy.

When I first got involved in advocacy in 2016, it was as a storyteller, working to save the Affordable Care Act. James benefited from a provision of the ACA that banned health insurance companies from imposing “lifetime limits” on medical care. Because James spent most of the first year of his life in the hospital and in a nursing home, he exceeded the cost that would have been his lifetime limit when he was only a few weeks old.

As I got more involved, I realized that what I really love is the details. I like reading the details of Medicaid Home and Community Based Services waivers–these are the state programs that give kids access to Medicaid services at home. While the federal government establishes a general set of rules, every state designs its own programs, so figuring out what the rules are for your state can be confusing. I like helping people figure out what’s going on with their own state waivers and figuring out who to contact to fix things.

You can reach out to me at jenny@littlelobbyists.org to talk about:

How can Medicaid help disabled kids live at home with their families.

What other programs help disabled children access their full civil rights in the community.

How Medicaid can help disabled young adults who are aging out of the pediatric care system.

I’m excited to work with the team at Little Lobbyists so that our kids can write their own stories!

Jenny McLelland is Little Lobbyists’ Policy Director for Home and Community-Based Services.