25 Years of Olmstead Rights: James & Jenny McLelland’s Story

Jenny McLelland (l) wearing a pink suit, James McLelland (c) wearing a dark suit, and Alison Barkoff, ACL Administrator & Asst Sec for Aging, stand in a sandstone hall at the Justice Dept in DC.

Today, June 22, 2024, marks the 25th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark case, Olmstead vs. L.C., which affirms the right of disabled people to use their state Medicaid benefits to live in their communities, rather than in institutions. The suit was brought by Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson against the State of Georgia, where Tommy Olmstead was the Commissioner of the Department of Human Resources.

Little Lobbyist James McLelland and his mom Jenny were invited to the U.S. Justice Department’s celebration of the Olmstead Decision to share their story. Like James, all of our disabled loved ones belong in their communities, with their friends and families.

The McLelland Olmstead Story

James: Hi! My name is James McLelland. I’m here today with my mom Jenny. My dad Justin and sister Josie are in the audience.

I’m a part of Little Lobbyists – a group that advocates for medically complex children (like me).

I am 13 years old and I live in Clovis, California. I just finished 7th grade. I play percussion in the school band. I can run a mile in 7 minutes 35 seconds. I’m fast. I’m a straight-A student too. I’m also disabled.

I know, I’m a real Renaissance kid.

I’m proud to be disabled. It’s part of who I am.

I have a tracheostomy. That’s the tube in my neck, it helps me breathe. Olmstead means I have a nurse that goes to school with me to make sure I keep breathing while I’m in class. I use a ventilator at night—that’s a machine that breathes for me—because I don’t breathe when I’m asleep. Olmstead means I have a nurse who comes to my house at night to manage the ventilator. If I roll over and the tubes disconnect, he reconnects everything to keep me breathing.

Being disabled means that I have to rely on other people-–it’s okay to rely on other people for care.

I’m here today because I’m an Olmstead success story—I’m getting the care I need to live my life the way I want to live it. I want to make sure that other disabled people have the same access to the community that I do.

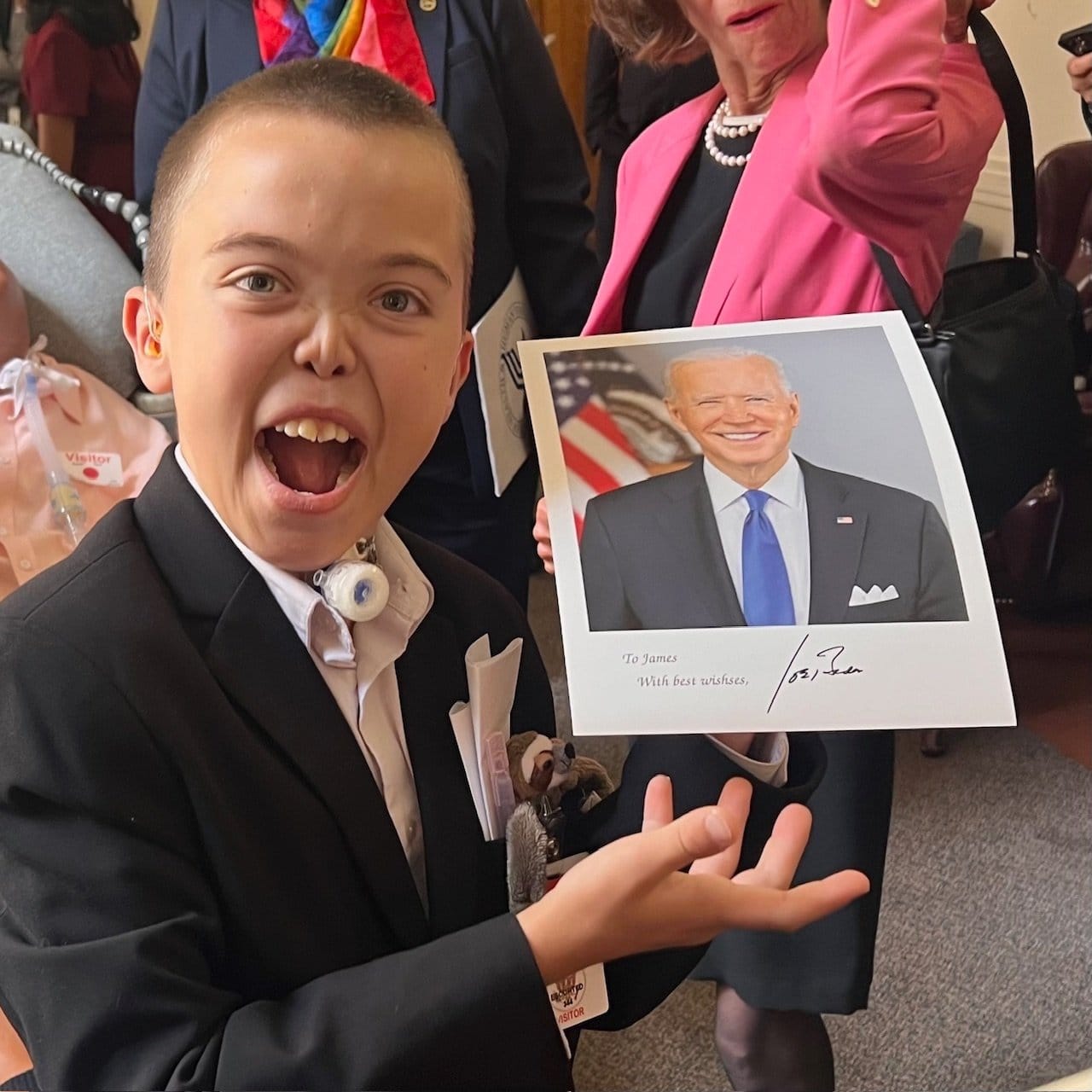

James reacts with enthusiasm to a signed photo of President Joe Biden he was given.

Jenny: Olmstead is what makes our family work. Olmstead means James can get the nursing care he needs to live safely at home with our family, attend school, and have a life. Today, James is an Olmstead success stor -–but that wasn’t always the case.

James spent most of the first year of his life in an institution. Institutionalization of children is not a thing of the past. It happened to our family, and it is still happening to medically complex kids just like James.

The doctors at the hospital where James was born didn’t give us the option to bring him home. They said if we brought him home he would die and it would be our fault. They said that even if he lived, his needs would be so overwhelming that our family would fall apart.

They didn’t mention Olmstead.

They didn’t tell us that Medicaid would pay for nursing care at home.

They told us to trust the system-–and the system was a pediatric subacute facility—an institution–200 miles from our home.

Putting James in the facility is the greatest regret of my life.

For a child with a tracheostomy, the biggest medical concern is keeping the airway open. But a baby crying isn’t a medical problem-–it’s just a thing that babies do.

You don’t solve the problem of a baby crying by suctioning away the secretions–you solve the problem by picking the baby up. In the facility, there was never enough staff to pick the crying babies up. If we weren’t at the facility, James would cry alone in his crib for hours. He would cry so long that he vomited, and he would lay in the vomit for long enough to burn his skin.

Institutional care provided 24/7 nursing. It met his medical care needs-–but it neglected his most basic human needs.

Olmstead advocacy is personal for me. I don’t want what happened to our family to happen to anyone else. As James grows into adulthood, I don’t want him to have to sacrifice his independence and live in a segregated facility to access care.

James (c) and Jeni (r) are seated at a long table with a royal blue cover, with a moderator to the left. They are on a stage in the Great Hall of the U.S. Department of Justice. Behind them is an American flag, a Justice Department flag, and a Health and Human Services flag. Above these is the U.S. Department of Justice seal with an eagle. On the far left is a large silver metal statue of Lady Justice, wearing a toga and holding up both arms.

How Could Olmstead Be Improved?

Jenny: Today, James is an Olmstead success story. He has access to Medicaid. We live in California, a state that pays parents and family caregivers in addition to paying nurses to handle complex medical care.

We’re able to be here today because Olmstead keeps our family together.

Olmstead means disabled people–like my son–have a civil right to access care in their own homes. Unless they can’t, because the program in their state has a waitlist.

Wait … civil rights can have waitlists?

Our life works because James has access to nursing care at home through a Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) waiver program.

There are disabled children and adults just like my son who can’t access care at home because they’re stuck on waitlists, sometimes for years.

What’s even worse? Every state has its own set of rules on who can qualify for HCBS waivers. That means some disabled people are locked out of getting care at home because their needs don’t check the right boxes in their state.

We’re a middle class family—my husband is a teacher and I’m a retired, injured police officer. In California, James qualifies for an HCBS waiver that provides Medicaid. If we ever moved, James would lose it.

Even when disabled people have access to HCBS waivers, low Medicaid reimbursement rates make it difficult to actually find nurses and caregivers. Most personal attendant caregivers make minimum wage or close to it.

The dignity of disabled people living at home and the dignity of care workers are two sides of the same coin.

The new federal rules that will require 80 percent of Medicaid dollars to go to the front line workers who are actually providing care is a great start. But we can’t fulfill the promise of Olmstead unless we make sure the Medicaid reimbursement rates are enough to pay caregivers and nurses a living wage.

When my son lived in institutional care, the system paid more than half a million dollars a year-–no questions asked. Providing him with nursing care at home is dramatically cheaper, but the system isn’t set up to make home care easy.

Disabled people who want to live at home have to figure out confusing paperwork, navigate a complicated system, and find their own caregivers to make life at home work.

Olmstead makes life work for disabled people, but we can make Olmstead work better.

James and Jenny McLelland are members of Little Lobbyists. Jenny is Little Lobbyists’ Policy Director for Home and Community-Based Services.