From Books to Belonging (by Alison Chandra)

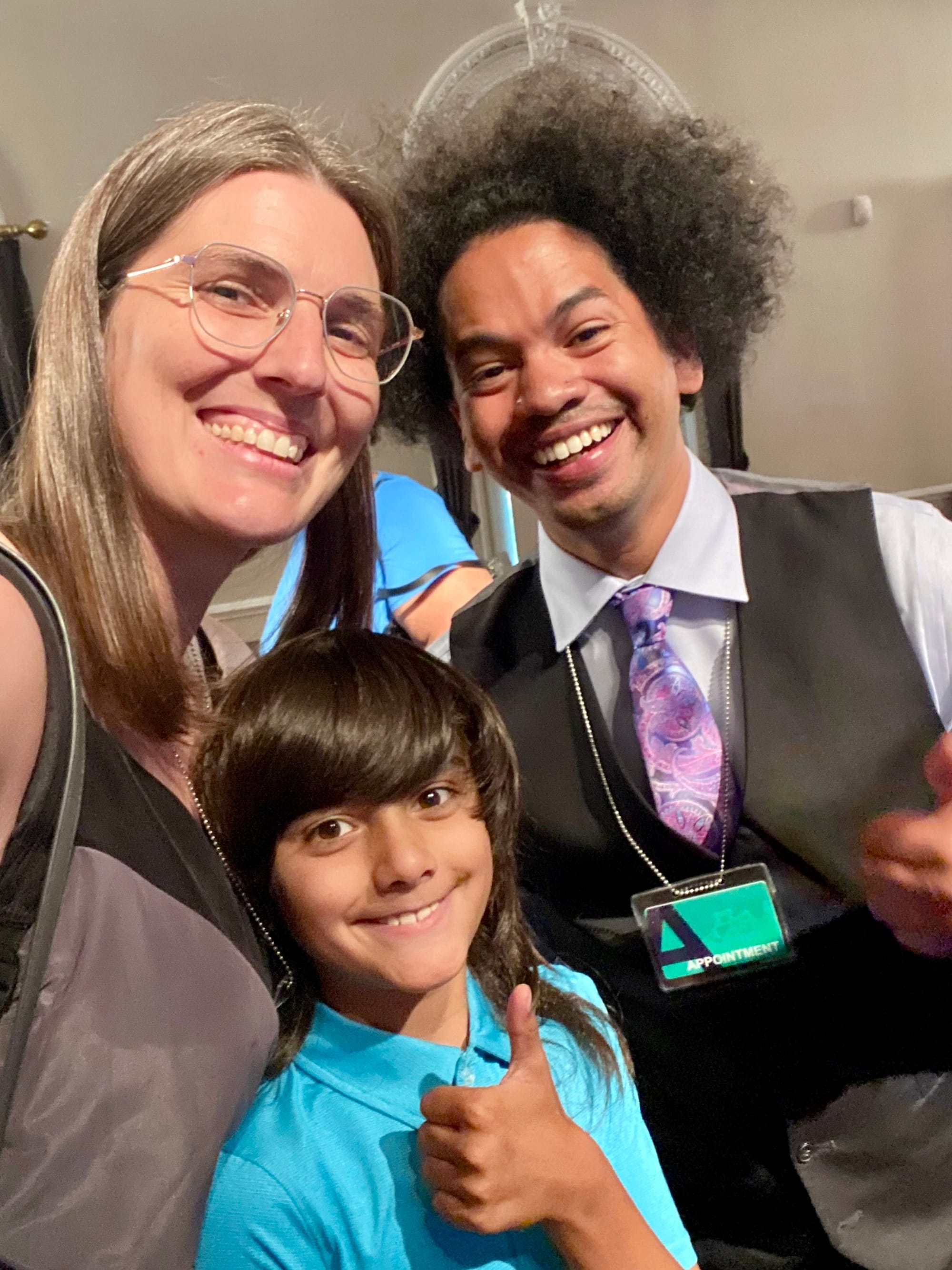

Alison, Ethan and Mychal (l to r) pose for a selfie. Ethan and Mychal are giving thumbs-up. All are smiling.

A few weeks ago, I sat in a room in the White House, surrounded by disabled advocates, and listened to a man named Mychal Threets speak about library joy. He was a panelist at the event, the White House Disability Pride Convening

I’d seen Mychal on TikTok before as “Mychal the Librarian,” drawn in by his wide smile and earnest delivery while he shared stories of library kids and library grownups and the ways he was working to make libraries a safe place for everyone. I nodded along, thinking how wonderful it was that there were advocates out there making the world a better place for disabled people, thinking about how grateful I was for organizations like Little Lobbyists who were doing the same work in the world of government.

When I walked into the room that day, my first ever visit to the White House, I thought I was there to advocate for my son, who, with multiple severe heart defects, a rare congenital disease, and a neurodivergent brain, certainly ‘belonged’ in a gathering of disabled people. I didn’t. I was just a little quirky. I liked things a certain way and had systems for how I organized my life, but disabled? That was for other people.

But what if I was one of the people Mychal was talking about?

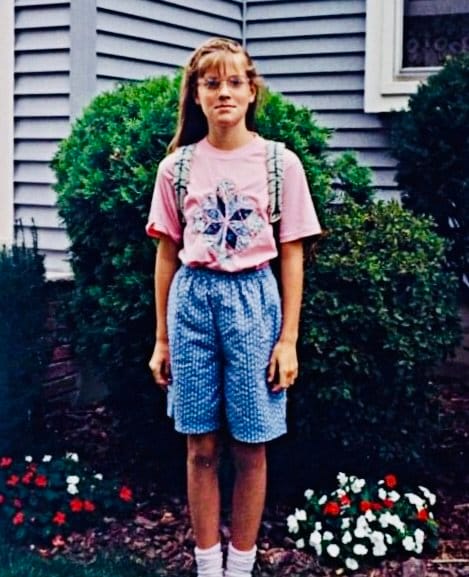

Growing up, I never felt like I belonged anywhere, least of all in my own skin. Little things that didn’t bother my brothers and sister were the end of the world to me. I seethed with anger, frustrated beyond rational expression when I couldn’t get my banana cut into exactly twenty pieces or when my mother asked me to wear an itchy skirt to school. Both my frequent meltdowns and my myriad systems were equally well known to my family, who endured both with a sort of baffled confusion. I understood what was going on about as little as they did, and so we all just muddled along together through my childhood.

My only saving grace was found between the pages of the books I’d started reading soon after I turned three. I read endlessly, some of my favorites over and over and over again until I had them nearly memorized. (I’m 41 now and still have the Jabberwocky running through my head on a near constant loop some days.) One of my happiest memories was when my mother explained that I was getting a custom-built bookshelf in my room, filled floor to ceiling with my treasured books. I arranged them all, from the Jane Austen box set my grandmother had gifted me in fourth grade to foreign language dictionaries to the journals filled with my own writings.

Alison circa 1992: her outfit is pink and blue and she’s posed against flowers and shrubs in front of a suburban home. She wears a backpack and looks very determined. Photo credit: Fiona Wilks.

By the time I reached middle school, the library was my safe haven. There wasn’t much of a place in the social hierarchy for the nerdy, awkward kid with a preposterous vocabulary, and so I’d hide among the stacks during lunch, pulling books off the shelves and escaping for a few precious moments to worlds I could pretend were made for me.

It took many years and my own son’s diagnosis of autism before I finally put the pieces together. Even now, after a kind woman put her hand on my shoulder and assured me that self-diagnosis is valid and that my son and I are an “excellent parent-child fit” (after I had pulled her into a deep dive about one of my son’s special interests), I still don't have an official piece of paperwork to tell me what I maybe should have known several decades ago.

I am autistic.

Words and language are my special interests. There was a reason that I felt more at home in libraries and in the imagined worlds of the books I devoured there than anywhere else. When I read, I’m not trapped in a world that’s too loud, a world where the seams of my socks never sit correctly and a soggy piece of cheese is a nightmare that I might need several business days to recover from.

Maybe you’re sitting there reading these words and nodding while I describe things that sound familiar to you, and you’re wondering how I went nearly forty years without having any idea that I was trying to navigate the world with an unrecognized disability. And I’d tell you that up until I sat in that room, I don’t think I had even come to terms with the fact that I have a disability at all.

Alison with her two children and her husband at a Heterotaxy Connection conference. The family wears conference name tags on blue lanyards around their necks and are posed in front of a conference backdrop with hand and heart icons, and the phrase, “Heterotaxy Connection,” “SEE: Support, Educate, Empower,” all in blue and yellow against a white background. Photo credit: Necia Sabin.

And then Mychal said something that rocked me. “As a librarian … what I seek to do every single day is to assure people that they do belong in the library. But not just the library, the world. It is okay to celebrate your disability.”

It was a blinding moment of clarity, one I’d been waiting for my entire life, and I found myself blinking back tears.

I belonged in that room. Sitting there watching ASL interpreters speak for the Deaf, listening to incredible speakers communicating using Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) devices, the sounds of happy stimming all around me, I realized for the first time that I belonged in a gathering of disabled people because I am disabled. And letting myself believe that for the first time in my life felt like coming home.

To quote Mychal, “Library joy is disability joy is all just human joy.” And as a disabled human who finds her joy between the pages of books, I approve this message.

Alison Chandra is a pediatric home health nurse and the mother to a medically complex child. She advocates for access to healthcare and disability justice from both sides of the bed.